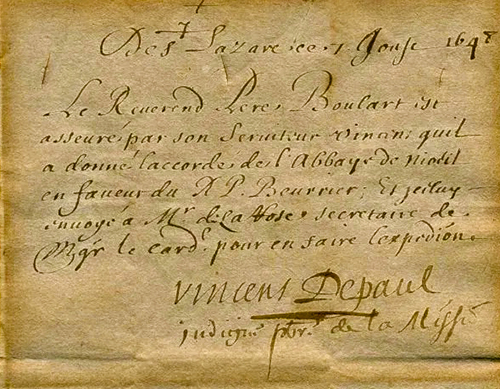

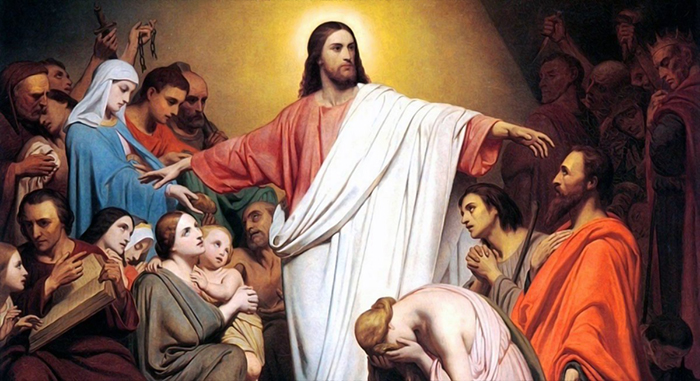

In today’s reading from the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus speaks about angels: “Take care that you do not despise one of these little ones; for, I tell you, in heaven their angels continually see the face of my Father in heaven.” We also see in the reading from Psalm 81 a beautiful statement of God’s protection being partly provided by the angels. For many, angels are simply viewed as cute, winged figures as have been depicted in art or as kindly old men like Clarence in the movie “It’s A Wonderful Life.” Belief in guardian angels has been in the mind of the Church since the earliest days and has been discussed at length by many noteworthy theologians such as St. Thomas Aquinas and St. Jerome. The angels Jesus spoke to today in Matthew’s gospel can take on a visible form, such as when the Angel Gabriel came to Mary, or remain unseen. But even in an unrecognized state, angels can still be communicative. Many beloved saints enjoyed such a relationship with their guardian angel. St. Pio of Pietrelcina (Padre Pio) and St. Gemma Galgani are two well-known examples. Such direct contact with a guardian angel was also the case for St. Catherine of Siena, St. Francis De Sales, and others. With this thought in mind, we close today’s reflection with a prayer to our Guardian Angel: “Angel of God, my guardian dear, to whom His love commits me here; Ever this day (or night) be at my side, to light, guard, and guide my way. Amen.”