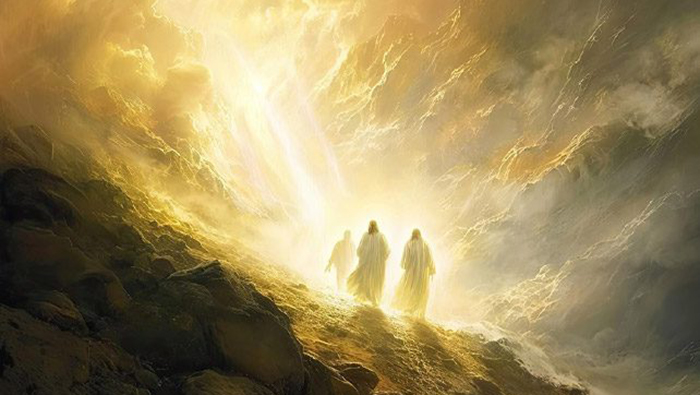

The Transfiguration, which we celebrate today, is an extraordinary moment and memory in Jesus’s life and in the Church’s birthing. We remember Jesus appearing suddenly to Peter, James, and John in a cloud of dazzling light, conversing with Moses and Elijah, and the voice of God naming him beloved Son. We rehearse the command of God, a mantra to guide our lives: “Listen to him.” Yet the Transfiguration is not only about God’s glory shining in Jesus. It is also about us, the hearers of the word, and our full adoption as sons and daughters of God when we look upon Jesus and receive the good news into our hearts. Today’s Communion antiphon proclaims: “When Christ appears, we shall be like him, for we shall see him as he is.” Think how desperately Peter would have needed to hear this message and take it into his heart. Imagine the regret and self-loathing Peter must have felt under the shadow of the crucifixion. Three times, he had said, “I do not know him.” Forgiven by Christ himself, Peter can now proclaim with confidence and without shame that the good news is not a fantasy or a “cleverly devised myth.” To see Christ “as he is” is at once to see ourselves as we truly are, like him, both broken and lifted up in glory. Because God has entered into our condition without reserve, even unto shame and violence and death, we can say of the good news, “It is reliable. It is a lamp shining in a dark place.” In the shadow of all our shame and moral failures, as crucifixions seem to stretch endlessly across the horizon of our broken world, the light of Christ rekindles our joy and courage for love “until the day dawns” and “the morning star rises” again in our hearts. God is Love. Christ is our way. The Spirit fires our courage and faith in all things. Come, Lord Jesus, come. – Dr. Christopher Pramuk