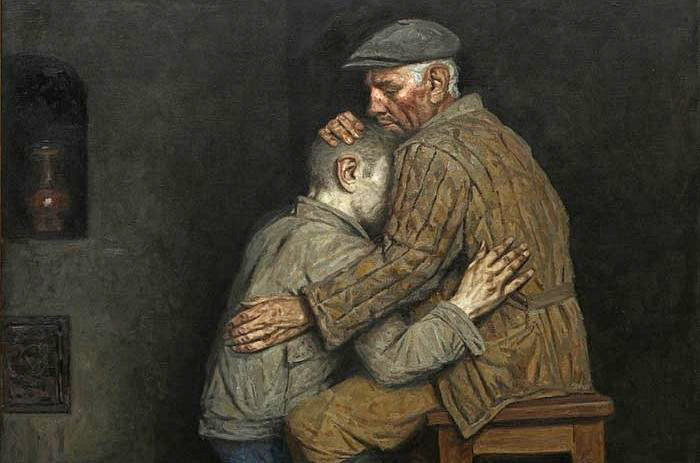

In John’s Gospel account of the resurrection, he tells the story of how on the morning of the first Easter, the Beloved Disciple runs to the tomb where Jesus has been buried and peers into it. He sees that it is empty and that all that’s left there are the clothes, neatly folded, within which Jesus’ body had been wrapped. And, because he is a disciple who sees with the eyes of love, he understands what this all means, he grasps the resurrection, and knows that Jesus has risen. He sees spring. He understands with his eyes. Hugo of St. Victor once famously said: Love is the eye. When we see with love, we not only see straight and clearly, but we also see depth and meaning. The reverse is also true. It is not for some arbitrary reason that, after Jesus rose from the dead, some could see him and others could not. Love is the eye. Those searching for life through the eyes of love, like Mary of Magdala searching for Jesus in the Garden on Easter Sunday morning, see spring and the resurrection. Any other kind of eye, and we’re blind in springtime. Without the eyes of love, we’re blind to both spring and the resurrection.[1]

[1] Excerpt from Fr. Ron Rolheiser’s reflection, “Seeing Spring and Easter,” April 2012.