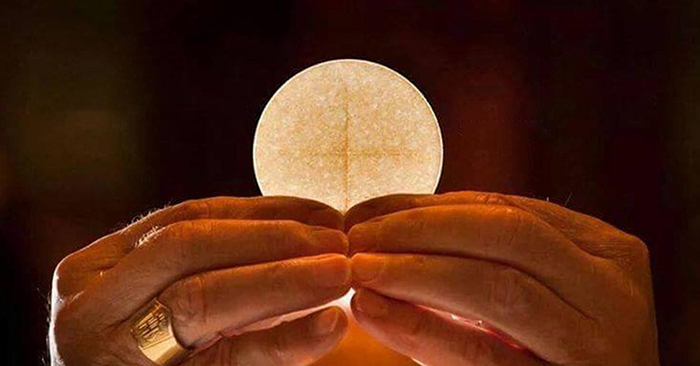

Bishop Robert Barron, writing in his book, “This Is My Body,” notes that the very earliest theology of the Eucharist is found in St. Paul’s First Letter to the Corinthians, penned probably in the early fifties of the first century, and it clearly brings forth this organic, participative quality. Paul speaks of the intense identification that is effected between Jesus and his Church precisely through the Eucharist: “The cup of blessing that we bless, is it not a sharing in the blood of Christ? The bread that we break, is it not a sharing in the body of Christ?” (1 Cor. 10:16). The evocative Greek term behind “sharing” is koinonia, meaning communion or mystical participation. Is this a hard doctrine? At the conclusion of the Eucharistic discourse, delivered at the synagogue in Capernaum, Jesus practically lost his entire Church: “When many of his disciples heard it, they said, ‘This teaching is difficult; who can accept it?’” (John 6:60). Again, if he were speaking only at the symbolic level, why would this theology be hard to accept? No one left him when he observed that he was the vine or the good shepherd or the light of the world, for those were clearly only metaphorical remarks and posed, accordingly, no great intellectual challenge. The very resistance of his disciples to the bread of life discourse implies that they understood Jesus only too well and grasped that he was making a qualitatively different kind of assertion. Unable to take in the Eucharistic teaching, “many of his disciples turned back and no longer went about with him” (John 6:66). Jesus then turned to his inner circle, the Twelve, and asked, bluntly enough: “Do you also wish to go away?” (John 6:67). There is something terrible and telling in that question, as though Jesus were posing it not only to the little band gathered around him at Capernaum, but to all of his prospective disciples up and down the ages. One senses that we are poised here on a fulcrum, that a standing or falling point has been reached, that somehow being a disciple of Jesus is intimately tied up with how one stands in regard to the Eucharist. In response to Jesus’ question, Peter, as is often the case in the Gospels, spoke for the group: “Lord, to whom can we go? You have the words of eternal life. We have come to believe and know that you are the Holy One of God” (John 6:68–69). As in the synoptic Gospels, so here in John, it is a Petrine confession that grounds and guarantees the survival of the Church. In the Johannine context, this explicit confession of Jesus as the Holy One of God is bound up with the implicit confession of faith in the Eucharist as truly the Body and Blood of the Lord. When the two declarations are made in tandem, John is telling us, the Church perdures. In light of this scene, it is indeed fascinating to remark how often the Church has divided precisely over this question of the Real Presence.